What bioavailability studies actually measure

When a generic drug is approved by the FDA, it doesn’t go through full clinical trials like the original brand-name version. Instead, it must prove it works the same way in the body. That’s where bioavailability studies come in. These tests don’t look at whether the drug cures a disease-they measure how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream and how fast.

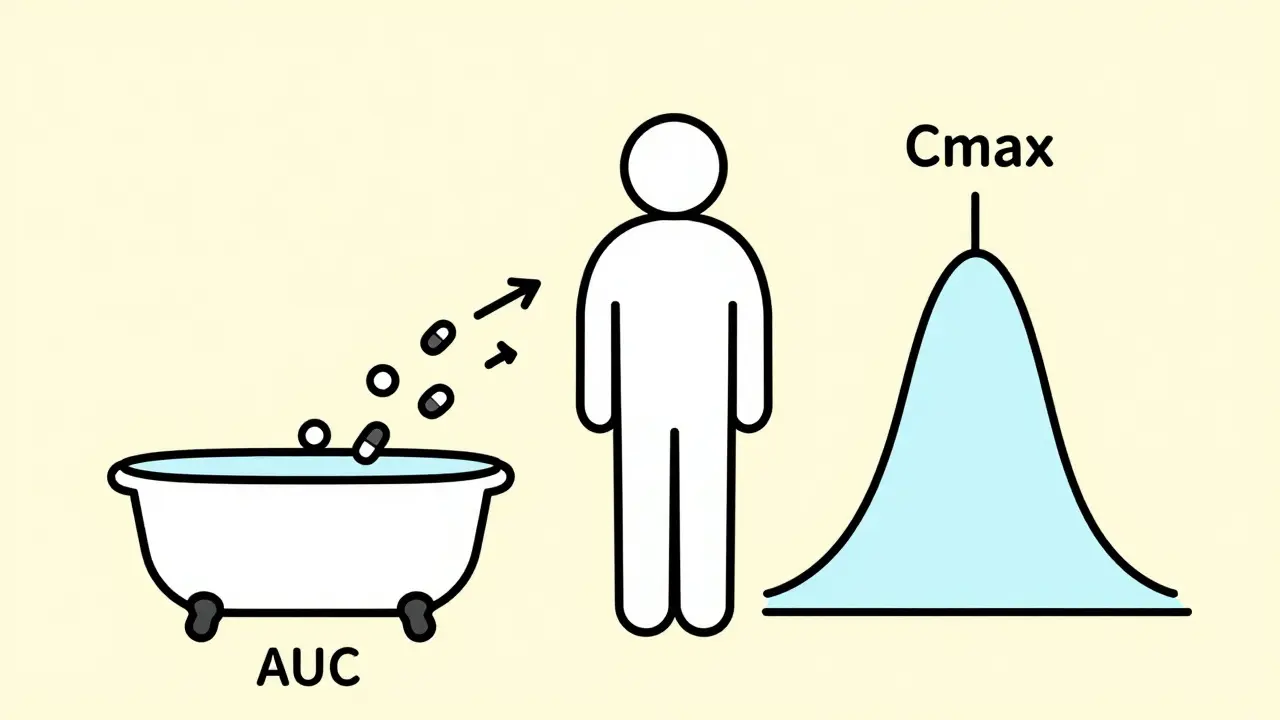

The two key numbers they track are AUC and Cmax. AUC stands for Area Under the Curve. It tells you the total amount of drug your body absorbs over time. Think of it like filling a bathtub: AUC is the total water in the tub after the faucet runs for a set time. Cmax is the highest point the water reaches-the peak level. This shows how quickly the drug enters your system. A third number, Tmax, records when that peak happens.

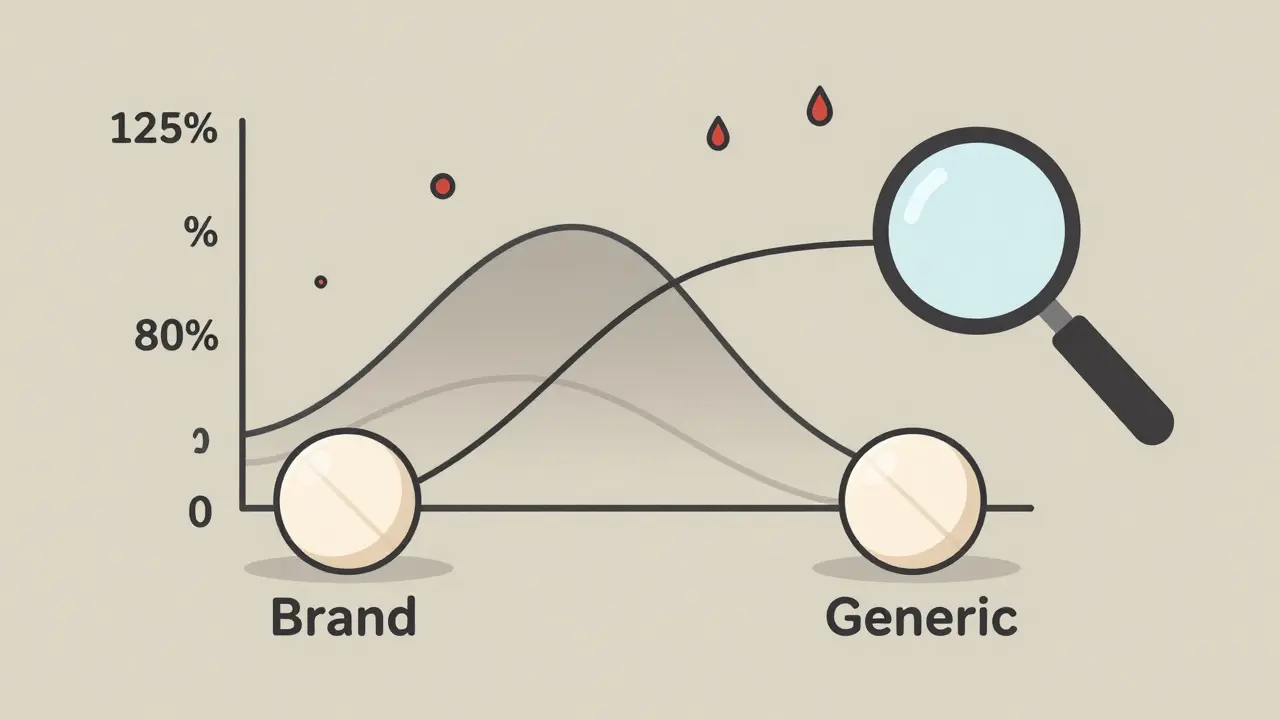

To get these numbers, volunteers take the generic and the brand-name drug on separate days, usually in a crossover design. Blood samples are drawn every 15 to 60 minutes for up to 72 hours. The samples are analyzed with highly precise lab equipment. The results must show that the generic’s AUC and Cmax fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s values. That’s not a guess-it’s a strict statistical rule based on decades of clinical data.

Why 80% to 125%? It’s not arbitrary

Many people assume the 80-125% range is just a convenient number. It’s not. It comes from real-world clinical experience. The FDA looked at thousands of drug comparisons and found that a 20% difference in absorption rarely affects how well a drug works or how safe it is. For most medications, your body can handle that small variation without any change in outcome.

But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine-even a 10% shift can be dangerous. That’s why the FDA requires tighter limits for these: often 90-111%. These drugs have a very small window between helping you and hurting you. A generic that passes the standard test might still be risky for these cases.

Studies show that out of 15,000+ generic approvals since 1984, only a handful have ever been linked to real clinical problems. In one study of over 3,000 patients on amlodipine, only three reported issues after switching to a generic-and all went back to normal when they switched again. That’s less than 0.1%. The system works for the vast majority.

How the tests are done-and why they’re so strict

A typical bioequivalence study involves 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They fast overnight, then take one pill, either the brand or the generic. Blood is drawn before the dose and then repeatedly afterward. The lab must be able to detect tiny amounts of the drug-sometimes down to a few nanograms per milliliter.

The testing method itself has to be validated. Accuracy must be within 85-115% of the true value. Precision can’t vary by more than 15%. If a lab’s equipment is off by even a few percent, the whole study is invalid. This isn’t a quick test-it’s a complex, expensive process. A single study can cost over $100,000 and take months to complete.

For extended-release pills, the FDA requires multiple time points to prove the drug releases slowly and evenly. For topical creams or inhalers, where the drug doesn’t enter the bloodstream much, they measure skin response or lung function instead. For some drugs, like those that dissolve quickly and are easily absorbed (BCS Class 1), the FDA may waive the human study entirely. That’s because the science says: if it dissolves the same way in a test tube, it will behave the same in the body.

When bioequivalence isn’t enough

Not all drugs play nice with the standard bioequivalence rules. Highly variable drugs-like tacrolimus or certain antivirals-absorb differently from person to person. One person might get 150% of the expected dose, another only 70%. For these, the FDA uses something called scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). It lets the acceptance range widen to 75-133% if the drug naturally varies a lot in the body. This isn’t a loophole-it’s a smarter way to handle drugs that behave unpredictably.

Some complex products still cause headaches. Take testosterone gel. Two gels might have the same active ingredient, but if one absorbs faster through the skin, the blood levels spike differently. That can affect mood, energy, or fertility. The FDA now requires special studies for these, sometimes using pharmacodynamic endpoints instead of just blood levels.

And then there’s levothyroxine. Thousands of patients rely on it for thyroid function. Even tiny differences in absorption can throw off hormone levels. That’s why some doctors prefer to stick with one brand. The FDA says generics are equivalent, but patient reports of fatigue or weight gain after switching are real-even if they’re rare. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s designed to catch the big problems, not every small variation.

What patients should know

If you’ve switched from a brand-name drug to a generic and noticed a change, you’re not imagining it. But it’s rarely because the generic failed the test. More often, it’s because your body is sensitive, or you’re on a drug with a narrow window. In most cases, going back to the original brand fixes it.

But here’s the bigger picture: 90% of Americans who take generics say they can’t tell the difference from brand-name drugs. Over 97% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They save the healthcare system billions every year. The science behind them is solid. The FDA doesn’t approve a generic unless it’s proven to work the same way.

Still, if you’re on a drug like warfarin, thyroid medication, or seizure control drugs, talk to your doctor before switching. Don’t assume all generics are identical. Some pharmacies may switch brands without telling you. Keep track of what you’re taking. If you feel different, speak up. Your doctor can request the brand if needed.

The future of bioequivalence testing

The FDA is working on new ways to make these studies faster and smarter. Instead of testing every new generic in humans, they’re using computer models to predict how a drug will behave based on its formulation. Early results show AI can predict bioavailability with 87% accuracy for 150 different drugs.

There’s also progress in in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC). If a pill dissolves in a lab test exactly like the brand, and the model says it will behave the same in the body, maybe we won’t need to test it in people at all. That could cut costs and speed up access to affordable medicines.

But the core hasn’t changed. The goal is still the same: make sure the generic delivers the same medicine, the same way, at the same rate. The science is mature, the rules are strict, and the results speak for themselves. Generics aren’t cheap copies-they’re scientifically validated alternatives. And for most people, they work just as well.

Comments (8)

Wow, this is one of the clearest breakdowns of bioequivalence I’ve ever read. I work in pharma logistics and see generics shipped daily, but never knew the science behind the 80-125% rule. That bathtub analogy? Perfect. I’ll be sharing this with my niece who’s in med school.

The fact that some generics cost 95% less but perform just as well is why I’ll never pay brand price again. Save your money, save your sanity.

Let’s be real-this whole system is a carefully curated illusion. The 80-125% range is a political compromise, not a scientific absolute. And let’s not pretend that 0.1% failure rate means nothing when you’re the one having a seizure because your levothyroxine was swapped mid-bottle.

Manufacturers game the system with excipients. Labs get lazy. The FDA is understaffed. This isn’t science-it’s regulatory theater with a side of corporate profit.

And don’t get me started on the waiver for BCS Class 1 drugs. That’s not science, that’s convenience dressed up as innovation.

Jonathan, you’re not wrong-but you’re also not helping. Yes, the system has gaps. But it’s still the best we’ve got, and it’s saved millions from going bankrupt on prescriptions.

Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater because one pharmacy switched your thyroid med without telling you. That’s a logistics failure, not a bioequivalence failure.

And hey, if you’re worried about tacrolimus or warfarin, then don’t switch. Simple. But don’t act like generics are a conspiracy. They’re not. They’re math, chemistry, and regulation doing their job.

Also, AI predicting bioavailability at 87% accuracy? That’s wild. In 5 years, we might not need human trials for half the drugs out there. That’s progress, not a loophole.

Stop being the guy who yells at the cloud. Be the guy who tells his doctor to keep the same generic. That’s the real power move.

Chris nailed it. The real issue isn’t the science-it’s the lack of transparency. Pharmacies swap generics like trading cards. No one tells you. No one asks you. You wake up feeling weird, and you assume it’s you.

My mom went from Synthroid to a generic, then back, then to another generic. Three different pills. Three different moods. She’s not ‘sensitive.’ She’s just not being informed.

Doctors should be required to specify the manufacturer on the script. Not just ‘levothyroxine.’ Name the brand. Otherwise, we’re all playing Russian roulette with our hormones.

USA think they own the science? 😂 I see this nonsense all day. In Nigeria, we get generics that cost $0.02 per pill and work better than your $10 brand-name junk. Your FDA is slow, expensive, and full of corporate lobbyists.

We don’t need 72-hour blood draws. We need pills that don’t dissolve into chalk in the heat. Your system is rich people’s theater. We fix drugs with common sense, not $100K labs.

Also, levothyroxine? My aunt takes Nigerian-made levothyroxine. She’s fine. Your ‘narrow therapeutic index’ is just your way of charging more.

Stop pretending your way is the only way. 🌍💊

Irebami, I hear you. And I get why you’re frustrated. But let’s not throw the whole global system under the bus because of bad packaging or heat degradation in transit.

The FDA’s rules aren’t perfect, but they’re based on real data. Your country’s generics save lives too-and that’s awesome. But if you want them to be *consistently* safe, you need the same rigor.

Imagine if every country had its own standard. You’d have 200 versions of metformin. Who’d know which one works? Who’d trust any of them?

Let’s push for better global standards-not to copy the FDA, but to build something that works for everyone. Even the guy in Lagos who needs his antiretrovirals to not turn to dust in the sun.

Generics work. Trust the data. Talk to your doctor if something feels off. That’s it.