When you take two medications at the same time, something unexpected might be happening inside your body. It’s not always obvious, but one drug could be making the other stronger, weaker, or even dangerous. This isn’t rare - it’s common. In fact, about one in five older adults in Australia are taking five or more medications, and each extra pill increases the chance of a hidden clash between drugs. These are called drug-drug interactions - and understanding how they work can save your life.

What Exactly Is a Drug-Drug Interaction?

A drug-drug interaction (DDI) happens when one medication changes how another one behaves in your body. It’s not just about side effects. It’s about chemistry, biology, and timing. One drug might speed up, slow down, or block the way another drug is absorbed, processed, or removed. Or, two drugs might team up in a way that amplifies their effects - sometimes dangerously.

There are two main types: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic. The first is about what your body does to the drug. The second is about what the drug does to your body - together.

Pharmacokinetic Interactions: How Your Body Handles the Drugs

Think of pharmacokinetic interactions like traffic control in your bloodstream. Drugs have to get absorbed, travel through your body, get broken down, and then leave. One drug can mess with any of those steps.

Absorption - Some drugs change the pH of your stomach or slow down gut movement. For example, antacids like Tums can make it harder for antibiotics like ciprofloxacin to get into your system. If you take them together, the antibiotic might not work as well.

Distribution - Many drugs stick to proteins in your blood, like a taxi clinging to a passenger. If two drugs both want to ride the same protein, one can push the other off. Warfarin, a blood thinner, is a classic example. When it’s pushed off its protein by drugs like ibuprofen, more free warfarin floats around - increasing bleeding risk.

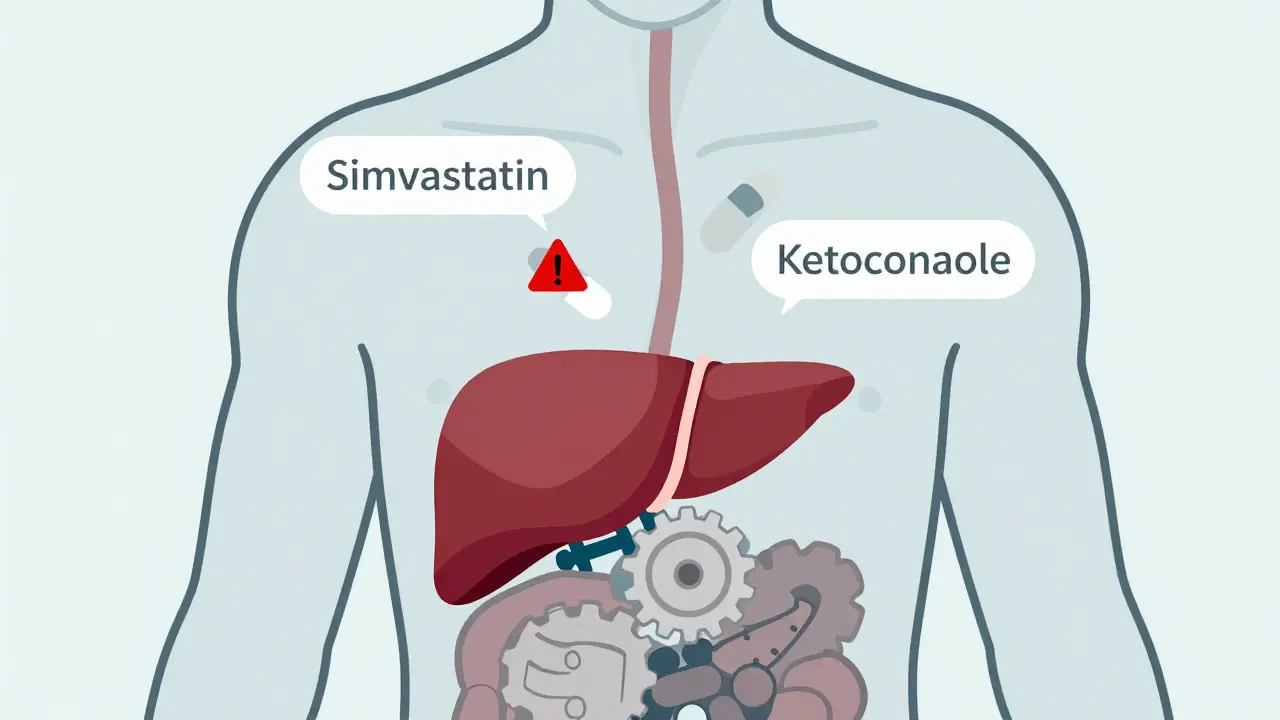

Metabolism - This is where most serious interactions happen. Your liver uses enzymes - especially the CYP450 family - to break down drugs. The most important one is CYP3A4. It handles about half of all prescription medications. If a drug blocks this enzyme (an inhibitor), other drugs pile up. If it speeds it up (an inducer), the other drug gets cleared too fast.

Take simvastatin, a cholesterol drug. If you take it with ketoconazole (an antifungal), CYP3A4 gets blocked. Simvastatin levels can jump 10 to 20 times higher. That’s not just a side effect - it’s a ticket to rhabdomyolysis, a condition where muscle tissue breaks down and can fry your kidneys.

On the flip side, St. John’s Wort - a popular herbal supplement - turns on CYP3A4. It can slash the levels of birth control pills, cyclosporine (used after transplants), and even some antidepressants. People think herbal means safe. It doesn’t.

Excretion - Your kidneys and liver flush drugs out. If one drug clogs the pipes, others back up. For example, the antibiotic trimethoprim can block the kidney’s ability to clear creatinine and digoxin. That’s why doctors check kidney function before prescribing these together.

Pharmacodynamic Interactions: When Drugs Team Up (or Fight)

Here, drugs don’t change each other’s levels - they change how your body responds to them. Two drugs might hit the same target in your brain, heart, or nerves.

Synergistic effects - This is when two drugs multiply each other’s action. A scary example: combining fluoroquinolone antibiotics like levofloxacin with macrolides like azithromycin. Both can prolong the QT interval - a timing measure in your heart’s rhythm. Together, they raise the risk of torsades de pointes, a life-threatening arrhythmia, by nearly six times.

Another example: ACE inhibitors (like lisinopril) and potassium-sparing diuretics (like spironolactone). Each raises potassium a little. Together, they can spike potassium levels by 1.0-1.5 mmol/L. That’s enough to stop your heart.

Antagonistic effects - One drug cancels out the other. For instance, beta-blockers like metoprolol and decongestants like pseudoephedrine. The decongestant raises blood pressure; the beta-blocker tries to lower it. They fight, and your blood pressure becomes unpredictable.

Who’s at Risk?

It’s not just older people - though they’re the most vulnerable. People taking five or more drugs have a 100% chance of at least one interaction. The Beers Criteria, used by doctors in the U.S. and Australia, lists 30 high-risk combinations for seniors. One of the worst? NSAIDs (like naproxen) with warfarin. Bleeding risk jumps 3 to 5 times.

But it’s not just age. Genetic differences matter too. About 7% of people are “poor metabolizers” of CYP2D6 - meaning they break down codeine poorly. Codeine turns into morphine via CYP2D6. In these people, codeine does nothing. But if they’re also taking a CYP3A4 inhibitor like clarithromycin, the little morphine that does form sticks around longer - risking overdose.

On the flip side, “ultrarapid metabolizers” turn codeine into morphine too fast. Add a CYP3A4 inhibitor, and you get a morphine flood. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) now recommends avoiding codeine entirely in these patients.

How Are These Interactions Found?

Drug companies test for interactions before a drug hits the market. They start in test tubes - human liver cells, enzyme samples - to see if a new drug inhibits or induces CYP enzymes. If the numbers look risky, they move to healthy volunteers. They give the new drug with a known “probe” drug, then measure blood levels.

The FDA and EMA now require testing for interactions with common drugs like ketoconazole, rifampin, and grapefruit juice. They also look at transporter proteins like P-glycoprotein (P-gp). Verapamil, a heart drug, blocks P-gp. That’s why it can boost digoxin levels by 50-100%. That’s not a coincidence - it’s a warning sign.

But here’s the problem: real life is messy. People take herbs, over-the-counter meds, alcohol, and food. Grapefruit juice alone can block CYP3A4 for days. One glass with simvastatin? Risky. Two glasses? Dangerous.

What Happens in Real Life?

Back in 2021, the FDA analyzed 12,842 adverse event reports linked to drug interactions. The top three? Warfarin (28.7%), antidepressants (15.3%), and other anticoagulants (12.1%).

And it costs money. A 2019 study estimated preventable DDIs cost the U.S. healthcare system $1.3 billion a year - mostly from hospitalizations for bleeding or muscle damage.

Pharmacists are on the front lines. A 2021 study showed that when pharmacists reviewed patients’ full medication lists, they cut serious interactions by 37%. That’s not just good practice - it’s life-saving.

What About Technology?

Most hospitals and clinics have electronic health records that pop up alerts when a new prescription might clash with an old one. But here’s the catch: 80-90% of those alerts are false alarms. Doctors get tired of them. They click past. That’s called “alert fatigue.”

Some systems are getting smarter. Epic’s “Suggestive Warnings” in 2021 didn’t just say “risk.” It gave context: “This combo increases bleeding risk in patients over 70 with kidney disease.” That cut high-risk interactions by 22%.

And AI is coming. A 2021 study trained a machine learning model on 89 million electronic health records. It predicted drug interactions with 94.8% accuracy - far better than old rule-based systems. It’s not perfect, but it’s getting close.

What Can You Do?

You don’t need to be a doctor to protect yourself. Here’s what works:

- Keep a full list of everything you take - prescriptions, supplements, herbs, even occasional painkillers. Update it every time something changes.

- Bring that list to every doctor and pharmacist visit. Don’t assume they know what you’re taking.

- Ask: “Could this interact with anything else I’m on?” Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- Use trusted tools. The Liverpool HIV-Drug Interactions Checker is free and updated daily. It works for many non-HIV drugs too.

- Be wary of “natural” products. St. John’s Wort, kava, and garlic supplements can all interfere with meds.

- If you’re on warfarin, keep your vitamin K intake steady. Spinach, kale, broccoli - eat them consistently, not randomly.

The Future: Personalized Medicine

Soon, your genes might tell your doctor what drugs to avoid - not just because of interactions, but because of how you’re built. Pharmacogenomics is no longer science fiction. CPIC has published 22 guidelines linking genes to drug responses. If you’re a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer, clopidogrel (Plavix) won’t work for you. That’s not a guess - it’s a genetic fact.

And it’s not just about single drugs anymore. Polypharmacy - taking three or more interacting drugs - is now a focus of FDA guidelines. The future isn’t just avoiding bad combos. It’s predicting the net effect of your entire regimen.

Drug interactions aren’t a glitch. They’re a system. And like any system, the more parts you add, the more things can go wrong. But with awareness, tools, and a little caution, you can stay safe - even when you’re taking multiple medicines.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause dangerous interactions?

Yes. Common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, antacids, and even cold medicines can interact with prescription drugs. For example, ibuprofen with warfarin increases bleeding risk. Antacids can reduce absorption of antibiotics like tetracycline. Even acetaminophen (Tylenol) can stress the liver if taken with alcohol or certain antidepressants. Always check labels and ask a pharmacist.

Are herbal supplements safer than prescription drugs?

No. Herbal products like St. John’s Wort, ginkgo biloba, garlic, and green tea extract can be just as powerful - and dangerous - as prescription drugs. St. John’s Wort induces CYP3A4 and P-gp, which can make birth control, HIV meds, and transplant drugs fail. Ginkgo can thin the blood and increase bleeding risk with warfarin or aspirin. Just because it’s natural doesn’t mean it’s safe.

Why do some drug interactions take days to show up?

Some interactions aren’t immediate. Enzyme inducers like rifampin or St. John’s Wort take days to ramp up enzyme production. The effect builds slowly - you might feel fine at first, then suddenly get sick or have a drug stop working. Inhibitors can also have delayed effects if they build up in your system. That’s why monitoring over time matters.

Can food and drinks cause drug interactions?

Absolutely. Grapefruit juice blocks CYP3A4 and can raise levels of statins, blood pressure meds, and immunosuppressants. Alcohol can increase drowsiness with sedatives and raise liver damage risk with acetaminophen. High-sodium foods can counteract blood pressure meds. Even dairy can bind to antibiotics like tetracycline and prevent absorption. Always check if your drug has dietary warnings.

What should I do if I think I’m having a drug interaction?

Don’t stop taking your meds without talking to your doctor. But if you notice new symptoms - unusual fatigue, dizziness, bleeding, muscle pain, heart palpitations, or confusion - contact your pharmacist or doctor right away. Bring your full medication list. Early detection can prevent hospitalization. Most interactions are avoidable with the right information.

If you’re managing multiple medications, you’re not alone. But you don’t have to guess your way through it. Knowledge is your best defense.

Comments (14)

You people are so naive. You think reading a blog post makes you an expert? I've seen patients die from these 'common' interactions because they trusted their 'pharmacist' instead of doing real research. St. John’s Wort? That’s just the tip of the iceberg. The FDA is asleep at the wheel and Big Pharma is laughing all the way to the bank. You think your vitamins are safe? They’re not. They’re unregulated poison with a hippie label.

Interactions aren't accidents. They're systemic.

They don’t want you to know this, but every single drug interaction warning? Manufactured. The government and pharma want you dependent. Why? So they can keep selling you more pills. They don’t care if you live or die-they care if you keep buying. Grapefruit juice? That’s a natural detox. They banned it in hospitals because it breaks their profit model. Wake up.

ok but like… what if your doctor just doesn’t care? i had this one doc who looked at my list and said ‘eh, you’ll be fine’ and i was like… are you serious?? i’m on 7 things and he didn’t even blink. i think they’re just tired. or maybe they’re paid off?? idk but i’m scared now 😅

Thank you for writing this 🙏 i’ve been on 4 meds for years and never realized how much my tea and turmeric might be messing with them… i’m going to print this out and take it to my pharmacist tomorrow. you’re right-knowledge is power. and also… i’m so glad i’m not the only one who feels like a lab rat sometimes 💛

This is an exceptionally well-researched and necessary piece. The statistics on preventable hospitalizations are staggering-and entirely avoidable. I work in geriatric care and see this daily. The most effective intervention isn’t technology-it’s the pharmacist sitting down with the patient, reviewing every pill, every supplement, every glass of grapefruit juice. We need more of that. Not fewer alerts. More human attention.

One must interrogate the epistemological foundations of pharmacokinetic paradigms. The CYP450 system, as currently operationalized, is a reductive anthropocentric construct-ignoring the phenomenological lived experience of polypharmacy as ontological dislocation. The algorithmic surveillance of drug interactions merely reproduces biopolitical control under the guise of safety. One wonders: who benefits from the commodification of metabolic vulnerability?

I’ve been taking my meds for 15 years and never had a problem. All this talk about interactions is just fear-mongering. People in America are too scared to take anything. In India, we take five different pills with tea and curry and still walk to the market. You think your liver is special? It’s not. Your body knows what to do. Stop overthinking. Just take your pills and stop reading blogs. You’re making yourself sick with worry.

Who let this crap get published? This is why America’s falling apart. We’re so obsessed with overanalyzing every little thing that we forget how to just live. Back in my day, people took pills and didn’t need a 10-page essay to tell them it’s dangerous. You want to live longer? Stop taking so many damn pills. Simple. Not rocket science.

Thank you for sharing this. I’ve been nervous about my meds for years but didn’t know how to ask. I’m going to start keeping a list like you said-and I’m going to bring it to my next appointment. I feel less alone now. You’re right-this isn’t about being an expert. It’s about being careful. And that’s okay.

The real issue isn’t drug interactions-it’s the normalization of chronic pharmacological dependency. We’ve turned the human body into a machine that needs constant calibration. We don’t treat root causes. We layer pills on top of pills. And then we call it ‘healthcare.’ This is pharmaceutical colonialism disguised as science.

This is so helpful. I’m on three meds and two supplements and always felt guilty for questioning them. Now I know it’s not just me being paranoid. Asking questions isn’t rude-it’s responsible. I’m going to print this and put it on my fridge.

Thank you for the comprehensive breakdown. I’m a clinical pharmacist and can confirm that the most effective risk mitigation occurs when medication reviews are proactive-not reactive. The 37% reduction in serious interactions when pharmacists are engaged is not an outlier; it’s replicable. We need policy changes to embed pharmacists in primary care teams-not just as dispensers, but as integrative care partners.

I appreciate how this piece balances science with practicality. As someone who works with immigrant communities, I’ve seen how language and cultural norms make these interactions even harder to navigate. Many don’t know to mention herbal teas or traditional remedies. We need multilingual resources and community health advocates-not just digital alerts. Knowledge should be accessible, not algorithmic.