Why Your Doctor’s Notes Don’t Match How You Feel

You walk out of the appointment with a piece of paper that says "Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, E11.9". You don’t know what that means. All you know is you’re tired all the time, you’re always thirsty, and you’ve lost five pounds without trying. Your doctor wrote down a code. You wrote down a story. And somewhere in between, the real message got lost.

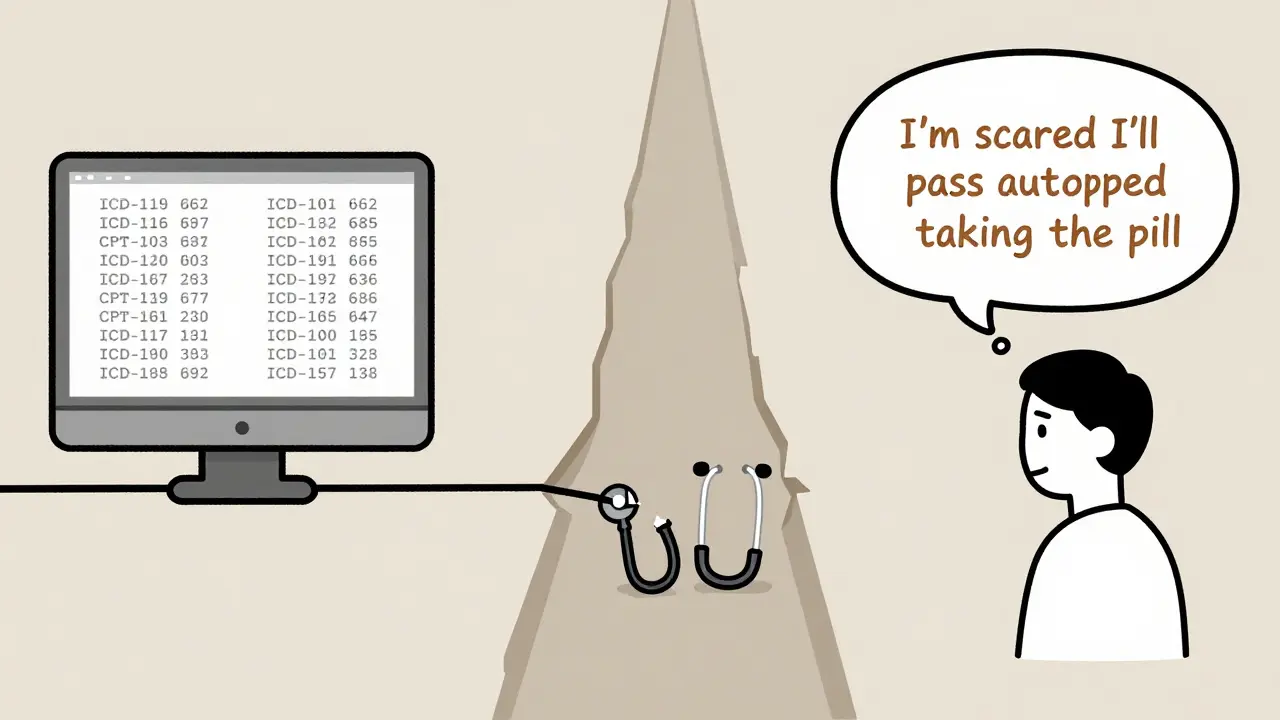

This isn’t just a misunderstanding - it’s a system-wide gap. Healthcare providers use standardized codes like ICD-10 and CPT to document what’s wrong. These codes help with billing, research, and tracking disease patterns. But patients? They describe pain, fatigue, fear, and confusion in plain words. And when those two versions of the same story don’t line up, mistakes happen.

How Providers Label Health: Codes, Not Conversations

Inside every electronic health record - whether it’s Epic, Cerner, or another system - your condition is stored as a string of numbers and letters. "Hypertension" becomes I10. "Asthma" becomes J45. "Depression" becomes F32. These aren’t meant for you. They’re meant for computers, insurers, and public health databases.

The American Medical Association keeps over 10,000 CPT codes for procedures. The World Health Organization’s ICD-10 system has nearly 70,000 diagnosis codes. Hospitals in the U.S. have been required to use ICD-10 since 2015. Why? Because accuracy matters for reimbursement. CMS pays hospitals based on these codes. If the code doesn’t match the documentation, the hospital loses money.

But here’s the catch: none of this helps you understand why you’re being prescribed metformin. Or why your blood pressure reading of 145/92 is "stage 1 hypertension." You’re not meant to read these codes. You’re meant to receive care based on them.

How Patients Experience Health: Stories, Not Systems

When patients talk about their health, they don’t use ICD codes. They say things like:

- "I feel like I’m dragging through molasses every morning."

- "My chest feels tight when I climb the stairs."

- "I’m scared I’m going to pass out at work."

- "I stopped taking the pill because it made me sick."

A 2019 study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that 68% of patients didn’t understand common medical terms. Nearly half didn’t know "hypertension" meant high blood pressure. Over 60% didn’t know "colitis" meant inflammation of the colon. These aren’t obscure terms - they’re the ones doctors use every day.

And when patients don’t understand, they make decisions based on fear, not facts. One patient on PatientsLikeMe wrote that her chart said "poorly controlled DM." She thought it meant she was a bad person, not that her blood sugar was too high. That’s not a mistake in judgment - it’s a failure in communication.

The Real Cost of Misaligned Labels

This isn’t just about confusion. It’s about safety.

Dr. Thomas Bodenheimer from UCSF says the language gap between doctors and patients contributes to 30-40% of medication errors. That’s not a guess. It’s based on years of tracking adverse events. When a patient doesn’t understand what "BID" means (twice a day), they might take their pill once. Or three times. Or skip it entirely because they think it’s "too strong."

The Institute of Medicine reported back in 2001 that communication failures led to 80% of serious medical errors. Fast forward to today, and little has changed. A 2022 survey by the American Medical Association found that 57% of patients felt confused by the terms in their medical records. One in three avoided follow-up care because they didn’t understand what was written.

And it’s not just patients who suffer. A 2023 Medscape survey showed that 64% of physicians spend 15 to 30 minutes per visit just explaining terminology. That’s time taken away from diagnosing, treating, or even listening.

Who’s Trying to Fix This - And How

Some places are making real changes. Kaiser Permanente started sharing full clinical notes with patients in 2010. They called it "Open Notes." By 2021, they saw a 27% drop in patient confusion and a 19% increase in people taking their medications correctly.

Mayo Clinic built "plain language" templates into their EHR. When a doctor types "myocardial infarction," the system automatically replaces it with "heart attack" in the version the patient sees. Their pilot program cut patient confusion by 38%.

The OpenNotes movement has grown to include 55 million patients across 350+ health systems as of early 2024. And it’s working. Early data shows 33% fewer disagreements between patients and providers about diagnosis.

Even the government is stepping in. The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 forced providers to give patients access to their notes - no redactions allowed. By April 2021, every hospital had to comply. That meant thousands of patients suddenly saw terms like "noncompliant" or "poor history" - words that sounded judgmental, not clinical.

What’s Changing on the Technical Side

Behind the scenes, new tech is trying to bridge the gap. The WHO’s ICD-11, rolled out globally in 2022, includes patient-friendly descriptions alongside every code. For the first time, "F32.1 Moderate depressive episode" also says: "You feel down most of the day, lose interest in things you used to enjoy, and have trouble sleeping."

Meanwhile, the HL7 FHIR standard - now used by 78% of major U.S. health systems - lets EHRs show two versions of the same note: one for providers, one for patients. It’s like having a translator built into the system.

And then there’s AI. Google Health’s Med-PaLM 2, released in 2023, can convert clinical notes into plain language with 72% accuracy. That’s promising - but not good enough yet. For medical use, we need 95% accuracy. We’re close, but not there.

By 2027, the American Medical Informatics Association predicts 60% of EHRs will have real-time translation tools built in. That could be the biggest shift since paper charts disappeared.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for technology to fix this. Here’s what actually works:

- Ask for plain language. After your doctor says "hypertension," say: "Can you explain that in words I’ll understand?"

- Use the teach-back method. After they explain something, repeat it back: "So if I take this pill twice a day, it’s to lower my blood pressure?" If you get it right, they’ll confirm. If you’re wrong, they’ll correct you - before you go home.

- Read your notes. If your provider uses a portal like MyChart, log in. Don’t just look at your lab results. Read the doctor’s note. If something sounds off, write it down and ask next time.

- Bring a friend. Two ears are better than one. Someone else might catch something you miss.

- Don’t be afraid to say "I don’t understand." That’s not weakness. It’s your right.

Healthcare isn’t broken because patients are confused. It’s broken because the system was built for efficiency, not understanding. But that’s changing. Slowly. And you have more power than you think.

What’s Next for Patient-Provider Communication

The future isn’t about replacing doctors with AI. It’s about giving patients the same clarity providers have. Imagine logging into your portal and seeing:

- "Your blood sugar is high → This means your body isn’t using insulin well."

- "You have high blood pressure → This increases your risk of heart attack or stroke."

- "The medicine you’re taking → This helps your body use insulin better."

That’s not science fiction. It’s already happening in clinics that prioritize health literacy. And it’s not just about words - it’s about dignity. When you understand your own health, you’re not a passive recipient. You’re a partner.

The labels are changing. The system is waking up. But the real shift starts with you asking: "What does that mean?"

Why do doctors use codes instead of plain language?

Doctors use codes like ICD-10 and CPT because they’re required for billing, insurance claims, and public health tracking. These codes are standardized so computers and insurers can process them quickly. But they’re not meant for patients - they’re designed for efficiency, not understanding. The system hasn’t caught up to the fact that patients need to understand their own health to manage it.

Can I ask my doctor to rewrite my medical notes in plain language?

Yes. You have the right to ask for clarification. Many clinics now offer patient-friendly versions of notes automatically, especially if they use OpenNotes or EHRs with plain language tools. If yours doesn’t, ask your provider to explain terms during the visit and request a simplified summary after. You can also ask for a printed version with plain language explanations.

What’s the difference between ICD-10 and CPT codes?

ICD-10 codes describe diagnoses - what’s wrong with you, like "Type 2 Diabetes" or "Hypertension." CPT codes describe procedures - what the provider did, like "office visit," "blood test," or "EKG." ICD-10 tells the system the problem. CPT tells the system what was done about it. Both are used for billing, but only ICD-10 directly relates to your condition.

How does OpenNotes help patients understand their care?

OpenNotes lets patients read their doctor’s visit notes in real time. Before, these notes were only for providers. Now, patients see everything - including terms like "noncompliant" or "poor history." That transparency forces providers to write more clearly. Studies show patients who use OpenNotes are less confused, take their meds more often, and feel more in control of their care.

Are there tools that translate medical jargon automatically?

Yes. Some EHRs now have built-in tools that replace medical terms with plain language for patient-facing documents. For example, "myocardial infarction" becomes "heart attack." AI tools like Google’s Med-PaLM 2 can also convert clinical notes, with 72% accuracy. While not perfect yet, these tools are improving fast and will likely be standard in most clinics by 2027.

What should I do if I see a term in my medical record that scares me?

Don’t panic. Write down the term and bring it to your next appointment. Many terms sound worse than they are - "poorly controlled" doesn’t mean you failed; it means your treatment needs adjusting. "Chronic" doesn’t mean hopeless; it means it’s long-term but manageable. Ask: "What does this mean for me? What can I do?" You’re not supposed to decode medical jargon alone.

Comments (14)