QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Ondansetron QT Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps clinicians assess the risk of QT prolongation when using ondansetron. Based on FDA guidelines and clinical evidence, it evaluates key risk factors to determine the safest course of action.

Risk Assessment

Current dosing appears safe for this patient profile.

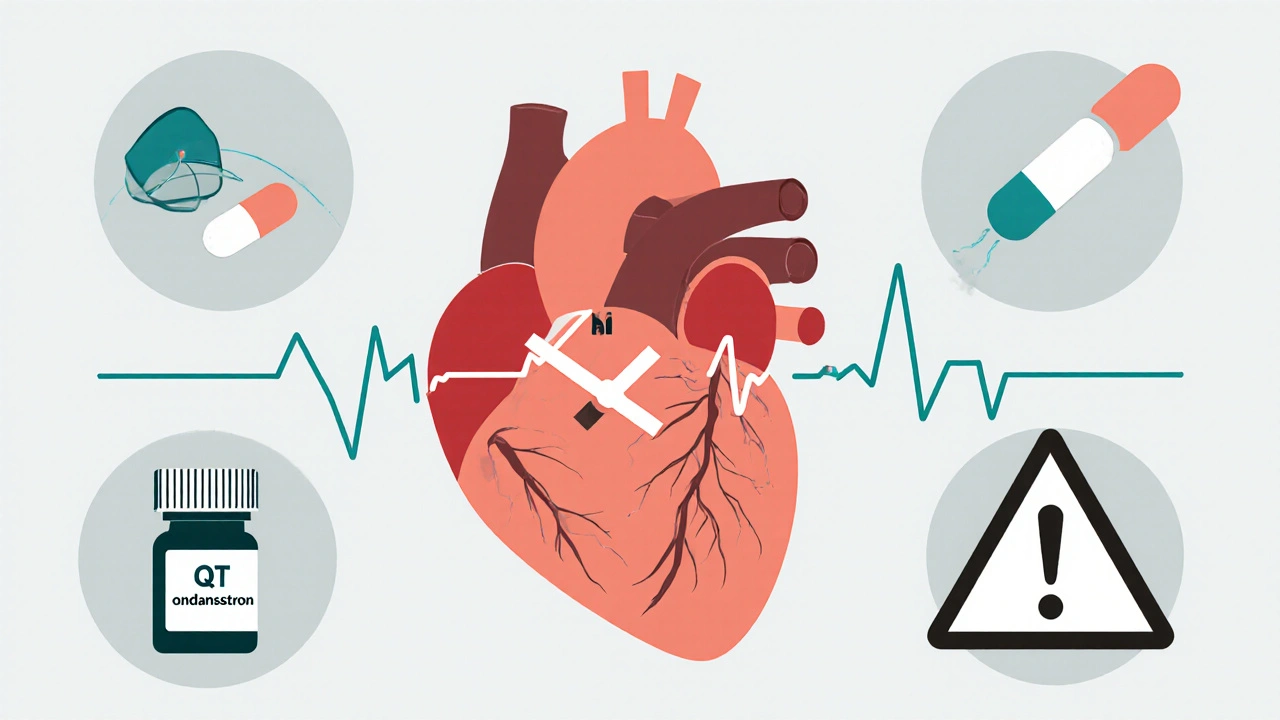

When you're feeling sick to your stomach after chemotherapy or surgery, ondansetron can be a lifesaver. It works fast, it’s effective, and for years, it was the go-to antiemetic in hospitals and clinics. But here’s the catch: ondansetron can also mess with your heart’s rhythm - and in some cases, it can be deadly. This isn’t speculation. It’s backed by FDA warnings, hospital protocols, and real patient outcomes. If you’re a clinician, a caregiver, or even a patient getting this drug, you need to know the real risks - and how to avoid them.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

Your heart doesn’t just beat randomly. It follows an electrical pattern: depolarization, contraction, then repolarization - the recharge phase. The QT interval on an ECG measures how long that recharge takes. When it stretches too long, your heart’s electrical system becomes unstable. That’s QT prolongation. And when it gets bad enough, it can trigger a wild, chaotic heartbeat called torsades de pointes (TdP). TdP isn’t just an ECG curiosity. It can turn into ventricular fibrillation and kill you within minutes if not treated. Ondansetron doesn’t cause this in everyone. But in the right conditions - high doses, existing heart problems, low potassium, or other drugs - it pushes the system over the edge. The FDA got serious about this in 2012 after a study showed IV ondansetron could lengthen the QT interval by up to 20 milliseconds. That’s not a small number. For every 10 ms increase in QTc, your risk of a dangerous arrhythmia goes up by 5-7%.Why Ondansetron Affects Your Heart

Ondansetron blocks serotonin receptors to stop nausea. But it also blocks something else: the hERG potassium channels in heart muscle cells. These channels are responsible for letting potassium out during repolarization. When they’re blocked, potassium stays inside longer, delaying the heart’s reset. That’s what stretches the QT interval. It’s not unique to ondansetron. Other antiemetics do this too - but not equally. Dolasetron? Higher risk. Granisetron? Much lower. Droperidol? Similar risk to ondansetron. Prochlorperazine? Moderate. But ondansetron is the most widely used, which makes it the most dangerous in aggregate. The numbers don’t lie. A 2011 study found that a single 32 mg IV dose of ondansetron caused a mean QTc increase of 20 ± 13 ms. That’s why the FDA banned single 32 mg IV doses. Even 16 mg IV can be risky. But here’s the twist: oral ondansetron? Much safer. A 24 mg oral dose doesn’t trigger the same spike. Why? Because the liver breaks down some of it before it reaches the heart.Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone who gets ondansetron will have problems. But certain people are walking into a minefield:- Patients with congenital long QT syndrome

- Those with heart failure or bradycardia

- People with low potassium or magnesium (common in chemo patients)

- Anyone taking other QT-prolonging drugs - like certain antibiotics, antidepressants, or antifungals

- Older adults, especially over 75 with existing heart disease

How Dosing Changed After the FDA Warning

Before 2012, 16 mg IV was standard. Now? Many hospitals cap it at 8 mg for high-risk patients. Some avoid IV entirely and go with oral or transdermal granisetron. The FDA’s official stance is clear: no single IV dose over 16 mg. But that’s the legal limit, not the safe one. Leading institutions like UCSF now recommend 8 mg IV max for anyone with cardiac risk factors. And they don’t just guess. They check:- Baseline ECG before giving the drug

- Electrolytes - potassium above 3.5 mEq/L, magnesium above 1.8 mg/dL

- History of other QT-prolonging drugs

Alternatives That Are Safer - and Just as Effective

You don’t have to use ondansetron. There are better options if cardiac risk is a concern.- Granisetron: Especially the transdermal patch. It has minimal QT effect. A 2013 study in Journal of Clinical Oncology showed it caused almost no QT prolongation compared to ondansetron.

- Palonosetron: Preferred by ASCO in 2023 for high-risk patients. At equivalent doses, it only increases QTc by 9.2 ms - less than half of ondansetron’s 20 ms.

- Dexamethasone: A steroid, not a serotonin blocker. Used alone or with lower-dose ondansetron. Many ERs now use it as first-line for low-risk nausea.

- Aprepitant/Fosaprepitant: NK1 receptor antagonists. No QT risk. Used for high-emetic-risk chemo. Market share grew 15% yearly since 2012.

What Hospitals Are Doing Now

The change hasn’t been easy. In 2011, only 37% of U.S. hospitals had formal ondansetron safety protocols. By 2022, that jumped to 92%. Here’s what they’ve built:- ECG monitoring for 4 hours after IV ondansetron in high-risk patients

- Automated alerts in electronic health records when QTc >450 ms (men) or >470 ms (women)

- Pharmacist review before any IV dose over 8 mg

- Staff training on QT correction formulas (Bazett’s vs. Fridericia)

What You Should Do - Patient or Provider

If you’re a patient:- Ask: “Is there a safer alternative to ondansetron?”

- Ask: “Will you check my electrolytes and ECG first?”

- If you have a history of heart rhythm problems, don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s “common.”

- Never give 32 mg IV. Ever.

- Limit IV ondansetron to 8 mg in patients over 65, with heart failure, or on other QT drugs.

- Always correct potassium and magnesium before giving it.

- Consider granisetron or palonosetron for high-risk patients.

- Use dexamethasone as a first-line option when appropriate.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. The NIH’s QT-EMETIC trial, running through 2024, is testing whether genetic testing (CYP2D6 poor metabolizers) can predict who’s most at risk. Early data suggests some people metabolize ondansetron so slowly, even 4 mg can be dangerous. The American College of Cardiology now recommends checking QTc before surgery if ondansetron is planned. That’s a big deal - it means this isn’t just an oncology issue. It’s a perioperative one. And the market is shifting. IV ondansetron use has dropped 22% since 2012. Sales of safer alternatives are climbing. Ondansetron isn’t going away - it’s still the most effective for acute nausea. But its role is shrinking. It’s no longer the default. It’s a choice - and one that needs to be made carefully.Can ondansetron cause sudden cardiac death?

Yes, in rare cases. Ondansetron can trigger torsades de pointes, a dangerous heart rhythm that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. This happens mostly with high IV doses (especially 32 mg), in patients with existing heart conditions, low electrolytes, or those taking other QT-prolonging drugs. Between 2012 and 2022, the FDA documented 142 cases of ondansetron-associated torsades, with 87% involving doses over 16 mg IV.

Is oral ondansetron safer than IV?

Yes. Oral ondansetron has a much lower risk of QT prolongation because the liver metabolizes part of the drug before it reaches the heart. The FDA states that single oral doses up to 24 mg do not require dosage adjustment. IV administration delivers the full dose directly into the bloodstream, causing a rapid spike in blood levels and greater cardiac effects.

What’s the maximum safe IV dose of ondansetron?

The FDA says no single IV dose should exceed 16 mg. But leading hospitals and guidelines now recommend limiting IV ondansetron to 8 mg for patients with cardiac risk factors - including those over 65, with heart failure, or on other QT-prolonging drugs. For low-risk patients, 8 mg is often sufficient and safer.

Should I get an ECG before taking ondansetron?

If you have any heart condition, are over 65, have low potassium or magnesium, or are taking other drugs that affect heart rhythm, yes. Many hospitals now require a baseline ECG before giving IV ondansetron. A QTc longer than 450 ms in men or 470 ms in women increases risk. Correction of electrolytes and ECG monitoring are now standard for high-risk patients.

Are there antiemetics without QT risk?

Yes. Dexamethasone (a steroid) and aprepitant/fosaprepitant (NK1 antagonists) have no known QT-prolonging effects. Granisetron, especially in patch form, and palonosetron carry significantly lower risk than ondansetron. For patients with cardiac risk, these are preferred alternatives, especially in chemotherapy or post-op settings.

Comments (6)

Man, I never realized how dangerous ondansetron could be. I had it after my knee surgery last year-no issues, but now I’m kinda paranoid. I didn’t even know they checked ECGs before giving it. Guess I got lucky. Still, I’m glad someone’s talking about this. Too many people just assume ‘common drug = safe drug.’

Let’s be clear: the FDA’s 16 mg IV limit is a legal fiction, not a safety threshold. Leading institutions like UCSF and Mayo Clinic have quietly adopted 8 mg as the new standard for all IV use, regardless of risk profile. The 2011 study showing a 20±13 ms QTc increase wasn’t an outlier-it was the baseline. And yes, oral is safer, but even oral 24 mg in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers can be risky. We’re talking pharmacogenomics here. If your hospital isn’t screening for CYP2D6 status in high-risk oncology patients, they’re operating in the dark ages.

Thanks for laying this out so clearly. As a nurse in a busy ER, I’ve seen both sides-patients who needed ondansetron to keep from vomiting during chemo, and the ones who ended up with QTc spikes we had to scramble to fix. We switched to palonosetron for anyone over 65 or on beta-blockers, and honestly? No one’s complained about nausea control. The real win? Fewer code blues. I’ve been pushing for mandatory ECGs before IV ondansetron, and it’s slowly catching on. It’s not about fear-it’s about being intentional.

Okay, so… I just read this whole thing… and I’m… wow. I didn’t know any of this. I’ve given ondansetron like, 20 times this month… and I didn’t check electrolytes once… 😳 I’m going to start checking every single time. And I’m going to tell my team. And maybe print this out and put it on the med cart. Thank you. Seriously. This could’ve been bad. Like, really bad.

Oh please. You’re all acting like ondansetron is the new thalidomide. The FDA warned about 142 cases in a decade? That’s less than 15 per year. Meanwhile, 200,000 people die from falls in hospitals every year-and no one’s banning walkers. This is fearmongering dressed up as ‘evidence.’ If you’re too scared to use a drug that works, maybe you shouldn’t be prescribing anything. My grandma took 16 mg IV and lived to 92. Coincidence? Maybe. But I’ll take my chances.

Y’all in the U.S. are overcomplicating everything. Back in my day, we gave 16 mg IV, checked for nausea, and moved on. Now you need an ECG, a pharmacist, a genetic test, and a 12-page consent form just to stop someone from puking? This is why healthcare costs are insane. If you’re too weak to handle a little QT prolongation, maybe you shouldn’t be in medicine. We don’t need more bureaucracy-we need more backbone.