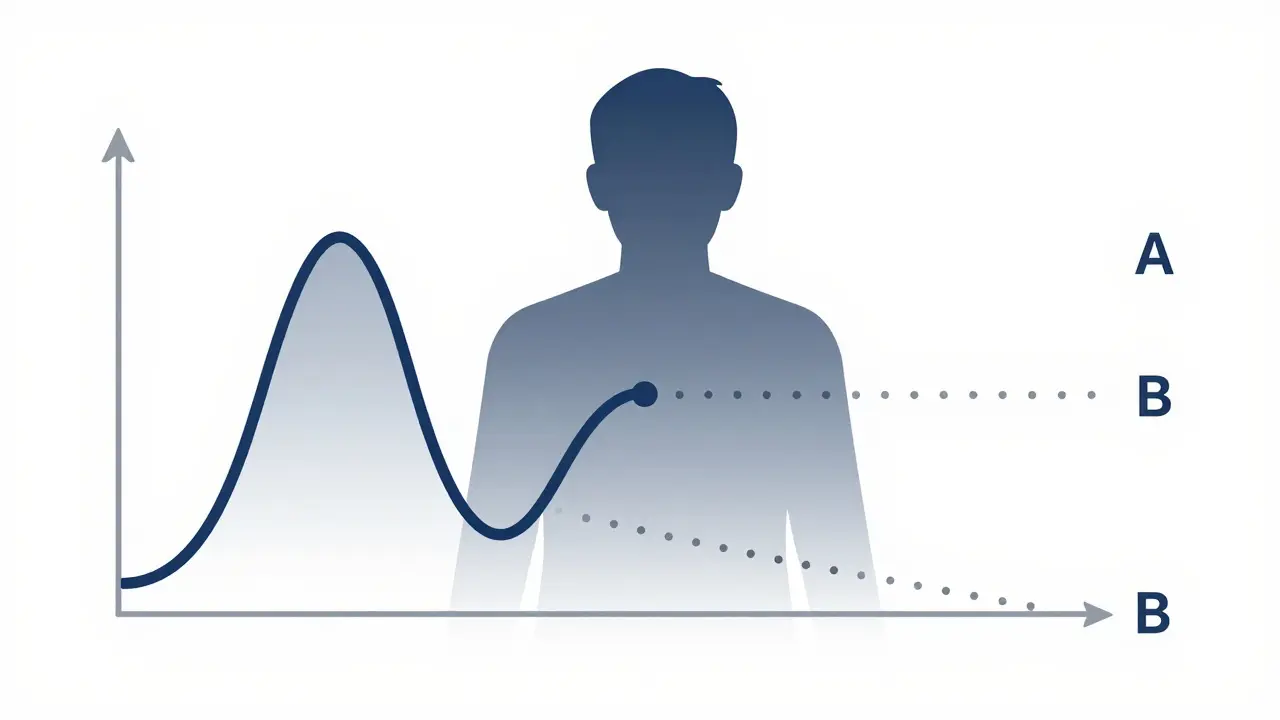

When a generic drug company wants to prove their version of a medication works just like the brand-name version, they don’t just guess. They run a crossover trial design - a precise, controlled experiment where each volunteer takes both drugs, one after the other. This isn’t just common practice; it’s the gold standard. Over 89% of all bioequivalence studies approved by the FDA in 2022 and 2023 used this method. Why? Because it cuts out the noise. Instead of comparing one group of people taking the generic to another group taking the brand, every person becomes their own control. That means age, weight, metabolism, and even sleep patterns don’t muddy the results.

How a Crossover Trial Actually Works

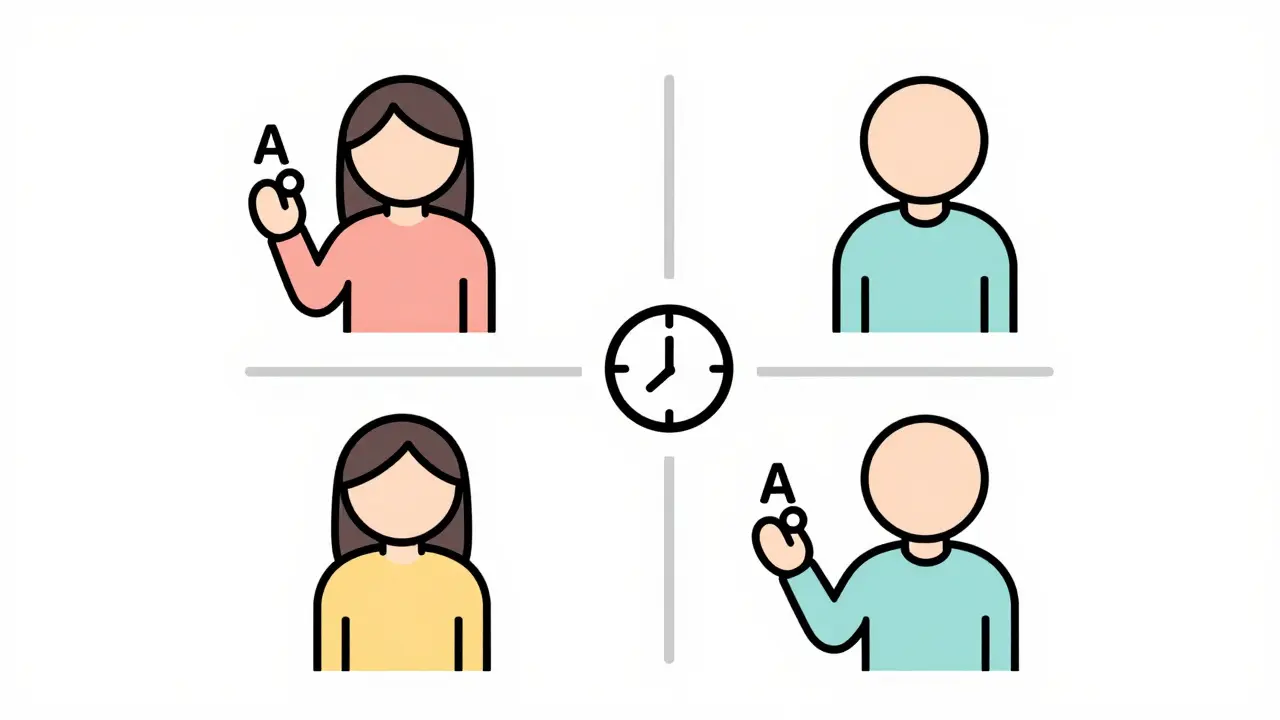

The simplest version is called a 2×2 crossover. Imagine 24 volunteers. Half get the brand-name drug first (call it A), then after a waiting period, they get the generic (B). The other half get the generic first (B), then the brand (A). This is often written as AB/BA. The key is randomization - you don’t assign who gets which sequence based on anything. It’s flipped like a coin. That way, if one group happens to be younger or healthier, it’s balanced out.

The washout period between doses is critical. It’s not just a break - it’s a reset. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require at least five elimination half-lives between treatments. For example, if a drug leaves your system in 12 hours, you wait 60 hours (five times 12). This ensures no trace of the first drug remains when the second one starts. If you skip this, you risk carryover effects - where the first drug still affects your body during the second phase. That’s one of the most common reasons bioequivalence studies get rejected.

Why This Design Beats Parallel Studies

Compare this to a parallel design, where one group gets only the generic and another gets only the brand. To get the same statistical power, you’d need six times as many people. Why? Because people vary wildly. One person’s liver processes drugs fast; another’s is slow. In a parallel study, those differences look like differences between drugs. In a crossover, those differences cancel out. You’re measuring change within the same person - not between different people.

That’s why crossover studies are cheaper and faster. A 2022 case on the BioBridges Forum showed a generic warfarin study saved $287,000 and eight weeks by using a 2×2 crossover instead of a parallel design. With only 24 volunteers needed (because the intra-subject CV was 18%), they avoided the 72 volunteers a parallel study would have required. That’s not just efficiency - it’s ethical. Fewer people are exposed to experimental conditions, and fewer resources are used.

What Happens When the Drug Is Too Variable?

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or certain epilepsy meds, have high intra-subject variability - meaning even the same person’s response changes a lot from one dose to the next. When the coefficient of variation (CV) hits above 30%, the standard 2×2 design starts to fail. The confidence intervals get too wide. You might miss a real difference - or falsely say two drugs are the same when they’re not.

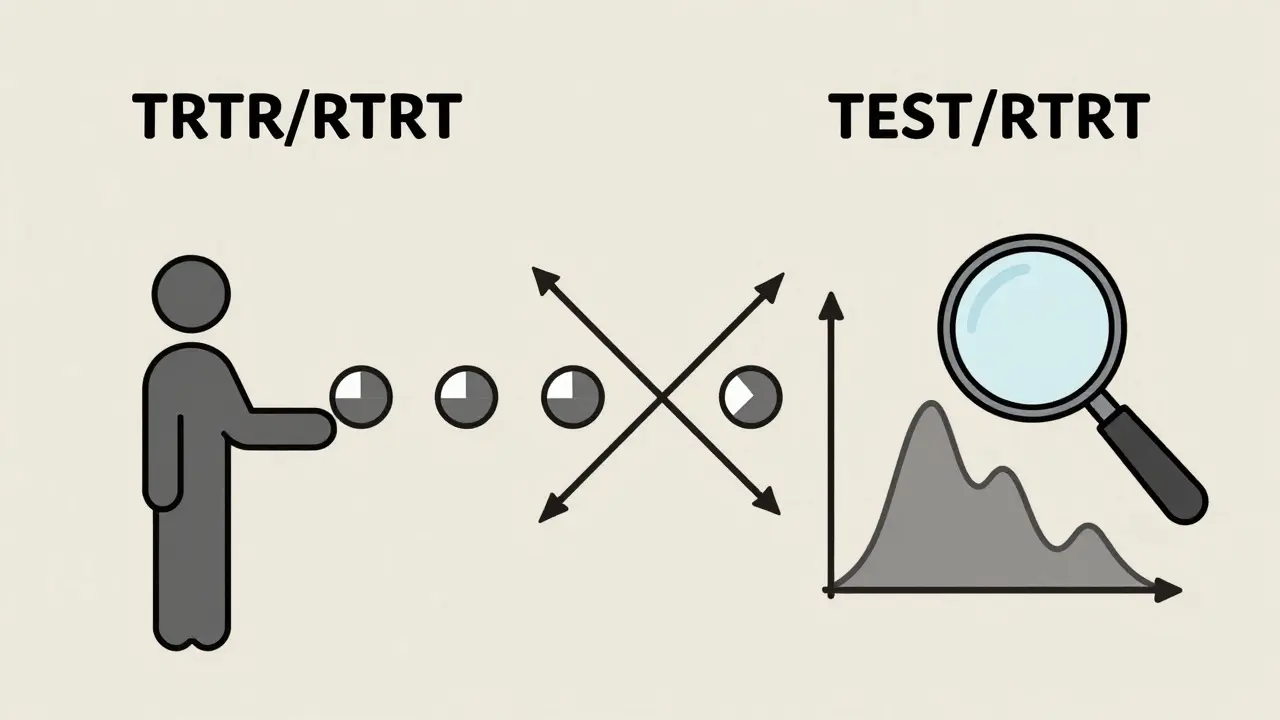

This is where replicate designs come in. Instead of two periods, you use four. The most common are the partial replicate (TRR/RTR) and full replicate (TRTR/RTRT). In a partial replicate, each person gets the reference (R) twice and the test (T) once - but in different orders. This lets you estimate how much the drug varies within each person for both the brand and the generic. The FDA allows wider bioequivalence limits (75%-133.33%) for these drugs using a method called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). Without replicate designs, you’d need 100+ volunteers just to get reliable data. With them, you can do it in 36-48.

One statistician on ResearchGate shared a hard lesson: his team’s first study failed because they used a 2×2 design for a drug with 42% CV. Residual drug levels from the first period skewed the second. They had to restart with a 4-period replicate design - costing an extra $195,000. That’s the cost of cutting corners.

Statistical Rules That Can’t Be Ignored

It’s not enough to just run the study. You have to analyze it right. The gold-standard method uses linear mixed-effects models - typically in SAS with PROC MIXED. The model checks for three things: sequence effects (did the order matter?), period effects (did time itself change the result?), and treatment effects (was there a real difference between the drugs?).

Most importantly, you must test for carryover. If the sequence-by-treatment interaction is significant, the whole study is invalid. That’s why regulators demand clear documentation of washout periods and concentration data. If even one participant has detectable levels of the first drug during the second period, the study can be rejected.

The bioequivalence threshold is strict: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) must fall between 80% and 125% for both AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration). For highly variable drugs using RSABE, those limits widen - but only if you’ve proven the variability is real and consistent. No guessing. No rounding. No fudging.

What You Can’t Do With Crossover Designs

There are limits. If a drug’s half-life is longer than two weeks - say, some osteoporosis drugs - a crossover design becomes impossible. Waiting five half-lives means months between doses. No volunteer will stay in a study that long. In those cases, parallel designs are the only option.

Also, crossover studies don’t work for drugs that cause permanent changes. If the first dose alters your body in a lasting way - like a vaccine or a chemotherapy agent - you can’t reset it. The design assumes the effect is temporary and reversible. That’s why it’s perfect for oral medications, but not for implants, injections with long-term effects, or gene therapies.

Industry Trends and the Future

The use of replicate designs is rising fast. In 2015, only 12% of highly variable drug approvals used RSABE. By 2022, that number jumped to 47%. The EMA’s 2024 update will make full replicate designs the preferred option for all highly variable drugs. Meanwhile, adaptive designs are creeping in - where researchers look at early data and adjust sample size mid-study. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions used this method, up from 8% in 2018.

Software tools like Phoenix WinNonlin make analysis easier, but open-source R packages like ‘bear’ offer more control - if you know how to use them. Many small CROs still struggle with proper modeling. The learning curve is steep. Biostatisticians need 6-8 weeks of specialized training beyond standard clinical trial courses.

Even with all the tech, human judgment still matters. The most successful studies aren’t the ones with the fanciest models - they’re the ones that respect the washout period, document every concentration level, and don’t assume carryover won’t happen. They test for it. They prove it’s gone. And they never skip the basics.

Real-World Impact

Behind every generic pill you buy is a crossover study. These trials ensure that a $5 version of a $50 drug works just as well. They keep healthcare affordable. But they’re not easy. One wrong washout, one missed concentration point, one flawed model - and the entire study fails. That means delays. Lost money. And patients waiting longer for safe, cheap medicine.

The system works because it’s rigorous. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we have. And for now, it’s not going anywhere. Experts predict crossover designs will remain the backbone of bioequivalence testing through at least 2035. As more complex generics hit the market - from inhalers to injectables - the designs will evolve. But the core idea won’t change: let the patient be their own control. That’s the power of this method.

What is the most common crossover design used in bioequivalence studies?

The most common design is the two-period, two-sequence (2×2) crossover, also called AB/BA. In this setup, half the participants receive the test drug first, then the reference drug after a washout period. The other half receive the reference first, then the test. This design is used in about 68% of standard bioequivalence studies because it’s efficient, cost-effective, and meets regulatory requirements for most drugs with low to moderate variability.

Why is a washout period necessary in a crossover trial?

A washout period ensures that the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. Regulatory agencies require at least five elimination half-lives between treatments. If drug residues remain, they can interfere with the second treatment’s absorption or metabolism - a problem called carryover effect. This distorts results and can invalidate the entire study. Validation of washout is often done by measuring plasma concentrations to confirm they fall below the lower limit of quantification.

When should a replicate crossover design be used?

A replicate crossover design (like TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) should be used when the drug has high intra-subject variability - typically when the coefficient of variation (CV) exceeds 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which permits wider equivalence limits (75%-133.33%) while still ensuring safety and efficacy. They’re especially common for drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, and certain antiepileptics where small changes in concentration can lead to big clinical differences.

Can crossover trials be used for all types of medications?

No. Crossover trials are not suitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over two weeks), where the required washout period would be impractical. They’re also unsuitable for treatments that cause permanent changes in the body, such as vaccines, gene therapies, or certain chemotherapies. In these cases, parallel-group designs are required because you can’t reset the patient’s physiological state between doses.

How do regulators determine if two drugs are bioequivalent?

Regulators like the FDA and EMA require the 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio (test/reference) for two key pharmacokinetic measures - AUC (area under the curve, total exposure) and Cmax (maximum concentration) - to fall within 80.00% to 125.00%. For highly variable drugs using RSABE, the limits can widen to 75.00%-133.33%, but only if the within-subject variability of the reference drug is proven to be high (CV >30%) and consistent across the study population.

Comments (13)

So basically this is why my generic blood pressure pill doesn't make me feel like a zombie anymore? That's wild. I always thought they were just copying the label.

This is one of those quiet miracles of modern medicine. Every time you grab a cheap pill at the pharmacy, someone ran a crossover trial so you didn't have to pay $500 for it. The science is elegant, the ethics are solid, and the savings? Astronomical. We should celebrate this stuff more.

bro. imagine being a volunteer in one of these studies. you take drug A, wait 60 hours like a good little lab rat, then take drug B. and you don't even know which is which. it's like being in a sci-fi movie where your body is a data point. 🤯

I... I didn't realize how much goes into this. The washout period, the statistical models, the carryover effects... I thought it was just 'same pill, cheaper price.' But now I see it's like a precision clockwork. So many things could go wrong. It's kind of beautiful, honestly.

all this math and still people get sick from generics. coincidence? i think not.

Okay, so let me get this straight - if a drug has a half-life of 12 hours, you wait 60 hours? That’s five full days of just... waiting? No coffee? No exercise? No life? And you’re locked in a clinical unit? That’s not science, that’s a prison sentence with extra steps. And don’t even get me started on the blood draws. I’d rather lick a battery.

This is why I love science. It’s not flashy, but it’s *rigorous*. Someone’s got to do the boring, tedious, math-heavy work so the rest of us can live. And yeah, sometimes it’s expensive to get it right - but imagine if they didn’t. We’d be taking guesswork pills. No thanks.

the 80-125% rule is a joke. my cousin took a generic and his anxiety went from 'meh' to 'i need to call a priest'. but hey, math says it's fine. 🤷♂️

Really appreciate this breakdown. I work in pharma logistics and never realized how much behind-the-scenes precision goes into making generics safe. The washout period detail? That’s the kind of thing that keeps people alive. Thanks for explaining it so clearly.

They call it 'crossover' like it's a fashion trend. Meanwhile, real people are stuck in clinical trials eating bland oatmeal for six weeks while being poked with needles. The system works? Sure. But it's not pretty. And someone's gotta pay for that $195k mistake when the CV hits 42%. Spoiler: it's not the pharma exec.

It's funny. We think of medicine as this big, heroic thing - surgeons, vaccines, breakthrough drugs. But the real quiet hero is the guy in the lab who made sure your $5 pill won't kill you. It's not glamorous. But it's sacred work.

Oh wow. So we're just trusting math to keep us alive? Cool. I'm sure the FDA's SAS models are just as reliable as my Uber driver's GPS. Also, 89%? That's not a gold standard - that's a popularity contest with a clipboard.

you guys are all missing the point. why not just test the drug on animals and call it a day? humans are too variable anyway. 🐶💉